The Coming US-China Armed Conflict?

History shows that America has been addicted to war while China's heart has been for peace.

The Trap of "the Thucydides Trap"

Ever since Harvard professor Graham Allison coined the term "the Thucydides Trap" in the summer of 2012 to capture the rising tensions between "a ruling America" and "a rising China", the term has almost been accepted as something like a Newtonian law defining US-China relations.

Yet, the Thucydides Trap is a western logic imposed on China that has an eastern logic.

What is "the Thucydides Trap"?

Thucydides (c. 460 - c. 400 BC) was an Athenian general who fought in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Athens). But he was known for writing The History of the Peloponnesian War, one of the earliest scholarly works of history.

In an article for the Financial Times

on 21 August, 2012, Allison quoted the following line from Thucydides' work:

“It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this inspired in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

Applying the variables "rise" and "fear" to China and the US respectively, Allison believes that "the Thucydides Trap" is "the best lens for understanding the competition between China and the United States", i.e. "when a rising China threatens to displace a ruling America, the most likely outcome is war."

Allison also examined 16 cases since 1500 involving a rising power threatening to displace a ruling power (see table below), and found that 12 of these ended in war while in four cases, including three from the 20th century, imaginative statecraft averted war.

Since then, "the Thucydides Trap" has been quoted countless times across the world, and despite Allison's clarification in his 2017 book Destined for War

that Thucydides' use of the word "inevitable" is clearly meant as hyperbole, so many Americans are now convinced that the war between the US and China is inevitable unless China's rise is contained by America through such measures as Trump's trade war.

For most Americans, the above makes perfect logical sense. Yet the logic has profound flaws.

What does Allison's work actually show?

1. The logic expressed by the Thucydides Trap is only part of the Western tradition. For weren't Athens and Sparta ancient Greek city-states, and was't Thucydides writing about ancient Greek culture, which actually laid the foundation of Western tradition?

2. Wasn't Japan's attack on Qing China in the late 19th-early 20th centuries the result of the former's rise as a Western-style military power following its wholehearted embracing of Western imperialism since the Meiji Restoration (see Bertrand Russell on the right)?

3. The pattern of the 16 cases also shows that

even Western nations, whose cultural tradition was founded on war, heroism, honour and glory, have

evolved towards peace over the course of 500 years.

"The Thucydides Trap" as quoted by leading American politicians

What America gets wrong about China and the rest of Asia | Professor David Kang

"The traditional civilisation of China had developed in almost complete independence of Europe, and had merits and demerits quite different from those of the West...

China may be regarded as an artist nation, with the virtues and vices to be expected of the artist: virtues chiefly useful to others, and vices chiefly harmful to oneself," says Bertrand Russell in his 1922 book The Problem of China

(p. 10)

"In considering the effect of the white races on the Far East as a whole, modern Japan must count as a Western product; therefore the responsibility for Japan's doings in China rests ultimately with her white teachers," (p. 14).

Conclusions on "the Thucydides Trap"

China's rise: 1. It is both legitimate and inevitable

for China to rise economically.2. The US was founded on the principle of human rights, and also champions it as such around the world. Doesn't each of the 1.4 billion Chinese people have a right to develop themself economically?3. If 1.4 billion Chinese people put into practice what they have learnt from the West in the past 40 years, work as hard as they always do, and keep on learning, it is inevitable that China's economy will eventually overtake that of America - which has a population only 1/5 of China's and, as part of its "decadence" in recent decades, has not invested much in its own citizens' education and learning.

America's fear: 1.

There is no need for Americans to fear China's economic rise. 2. Even if China's economy eventually overtakes America's, the US will still be, by far, the strongest country in the world, in terms of per capita GDP, technological power, and above all, military power. 3. It is also absurd to assume that China has ambitions to "rule the world" by taking over America's nearly 800 military bases in more than 70 countries and territories around the world. For,

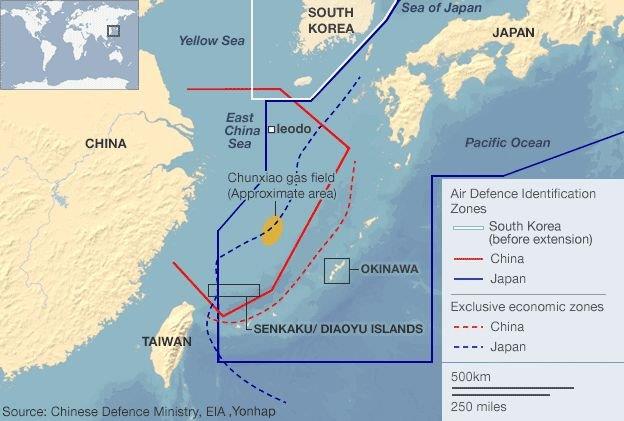

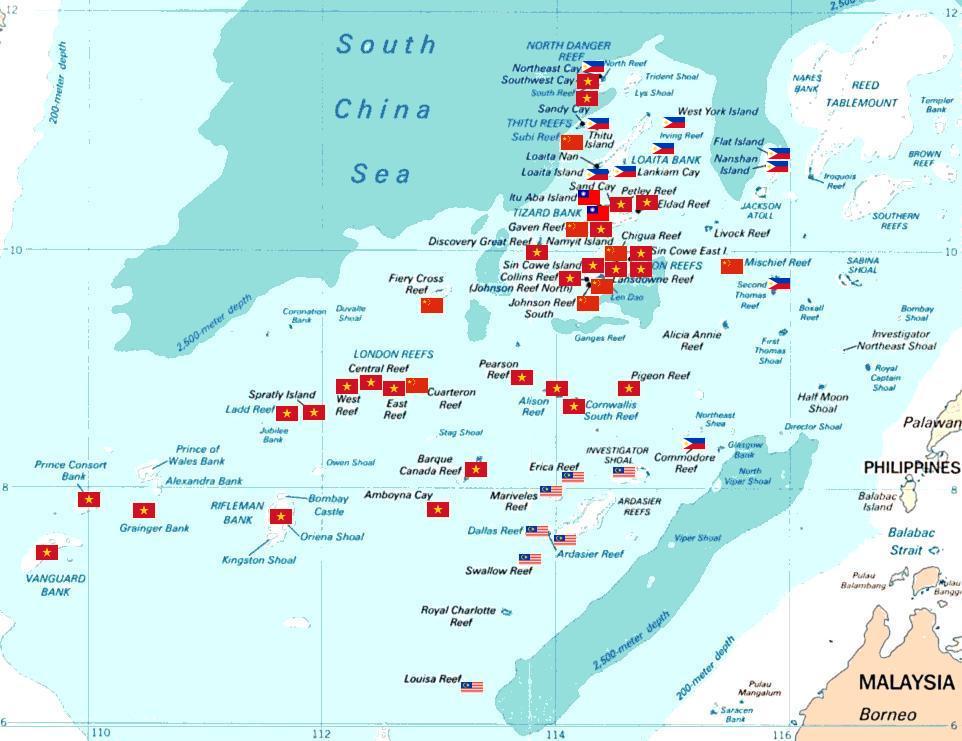

except to settle certain land and maritime border disputes in a reasonable fashion, China, in its cultural genes formed over thousands of years, has never had ambitions to conquer distant lands (see below).

Geography and Thought in the Beginning

Sea versus land: Different worlds, different thinkers

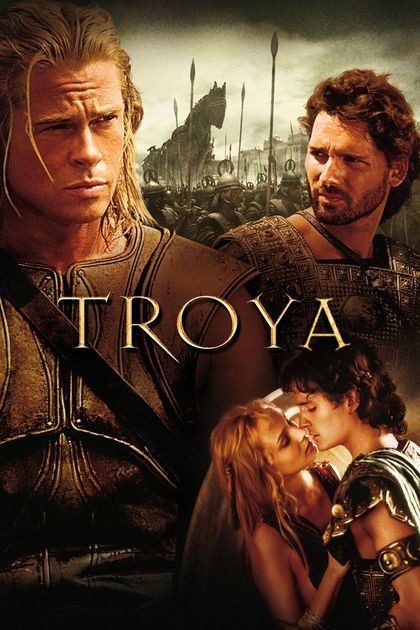

In the 2004 film Troy

adapted from the Iliad, there is an episode, where Achilles came to see his mother for advice on whether he should go to Troy to fight the war and she told him:

"If you stay in Larisa, you will find peace. You will find a wonderful woman. You will have sons and daughters, and they will have children. And they will love you. When you are gone, they will remember you. But when your children are dead and their children after them, your name will be lost. If you go to Troy, glory will be yours. They will write stories about your victories for thousands of years. The world will remember your name. But if you go to Troy, you will never come home. For your glory walks hand in hand with your doom. And I shall never see you again."

Achilles, of course, went to the war. But as his mother made clear, there was the second, alternative path for Achilles: staying in his homeland, having a family, and living a peaceful life. What she did not know, though, was that this path was what the ancient Chinese had been inspired to choose.

The Iliad:Glorifying war

The 《尚书》:Valuing harmony

Open the 15,000-line epic poem

Iliad

at random, chances are you will come upon the fighting of heroes. Often, it depicts the horrors of battle in great detail, perhaps even gleefully:

“He fell on his back in the dust, stretching out his hands towards his comrades, gasping. The man who had hit him, Peiros, ran up and struck him with a spear near his navel. Out poured all his guts onto the ground, and darkness came over his eyes.”

In fact, the central theme of the Iliad

is

the glorification of war.

War was something young men had to do as descendents of their family. They fought because their fathers fought and their children will fight as they have fought, like Hector and Andromache wish for their son Astyanax. Fighting also had its place in religion, with war being the method to be in a god’s presence, to interact with gods personally, to win their favour or, in Diomedes’ case, who himself is just a mortal, to even fight them. Warriors are “servants of the War-god Ares,” and battle is depicted as “the War-god’s deadly dance.”

War booty is constantly mentioned, and it is the cause of Achilles’ absence from the battlefield. Soldiers seem to have plenty of women at their hands, their cups filled with wine that is in constant supply to the army and feasts celebrated on a daily basis as oxen are sacrificed to the deities. Above all,

battle is the place “where men win glory,” with the ultimate ambition being

kleos,

fame that stays with you after death. Achilles shows bravery by going to war and killing Hector, although he knows this will inevitably result in his own death.

Composed around 700 BC, the

Iliad was to influence and inspire generation after generation of Westerners—from ancient Greeks and Romans to modern Europeans and Americans. Even today, the story of the

Trojan War is still one of the first and favourite stories Western children learn to read.

In fact, the central theme of the Iliad

is

the glorification of war.

War was something young men had to do as descendents of their family. They fought because their fathers fought and their children will fight as they have fought, like Hector and Andromache wish for their son Astyanax. Fighting also had its place in religion, with war being the method to be in a god’s presence, to interact with gods personally, to win their favour or, in Diomedes’ case, who himself is just a mortal, to even fight them. Warriors are “servants of the War-god Ares,” and battle is depicted as “the War-god’s deadly dance.”

War booty is constantly mentioned, and it is the cause of Achilles’ absence from the battlefield. Soldiers seem to have plenty of women at their hands, their cups filled with wine that is in constant supply to the army and feasts celebrated on a daily basis as oxen are sacrificed to the deities. Above all,

battle is the place “where men win glory,” with the ultimate ambition being

kleos,

fame that stays with you after death. Achilles shows bravery by going to war and killing Hector, although he knows this will inevitably result in his own death.

Composed around 700 BC, the

Iliad was to influence and inspire generation after generation of Westerners—from ancient Greeks and Romans to modern Europeans and Americans. Even today, the story of the

Trojan War is still one of the first and favourite stories Western children learn to read.

By contrast, in China, one of the first and favourite stories children learn to read (and recite) is “Yu the Great Taming the Waters”

(大禹治水, dayu zhishui).

It tells of ancient China being ravaged by a flood from the Yellow River. Yu's father, after being appointed by the emperor to tackle the problem, failed miserably because he tried to build higher banks to contain the waters. Learning from his father's lesson, Yu instead led the flood waters into the sea by removing obstacles to it, which he achieved by dividing the country into nine prefectures and delegating specific responsibilities to them. And in carrying out his task in thirteen years, he passed his home three times but never went in to greet his wife and children. In the end, the flood waters were tamed, agricultural fields expanded, and people all over the country could again live a peaceful life.

The story is told in the Shang Shu

(尚书, “the Book of Documents”), China’s earliest narrative. The book begins with Yao who became emperor at the age of twenty and was extolled as the morally perfect sage-king because of his human-heartedness and diligence. In his old age, he realised that his own son was not good enough to succeed him and therefore looked around for the best man available.

He was recommended a humble bachelor named Shun. Shun’s father was stupid; his stepmother deceitful; and his half-brother arrogant. Yet he lived in harmony with all of them.

On the strength of this recommendation, Yao gave Shun two of his daughters in marriage to observe his behaviour. Impressed by his virtue, Yao passed the throne to Shun and, before he died, told Shun “to impartially adhere to the middle way”

(允执厥中,

yun zhi jue zhong). During his reign, impressed by Yu’s qualities, including his success in taming the flood waters, Shun decided to pass the throne to Yu and, before his death, told Yu the yun zhi jue zhong.

It tells of ancient China being ravaged by a flood from the Yellow River. Yu's father, after being appointed by the emperor to tackle the problem, failed miserably because he tried to build higher banks to contain the waters. Learning from his father's lesson, Yu instead led the flood waters into the sea by removing obstacles to it, which he achieved by dividing the country into nine prefectures and delegating specific responsibilities to them. And in carrying out his task in thirteen years, he passed his home three times but never went in to greet his wife and children. In the end, the flood waters were tamed, agricultural fields expanded, and people all over the country could again live a peaceful life.

The story is told in the Shang Shu

(尚书, “the Book of Documents”), China’s earliest narrative. The book begins with Yao who became emperor at the age of twenty and was extolled as the morally perfect sage-king because of his human-heartedness and diligence. In his old age, he realised that his own son was not good enough to succeed him and therefore looked around for the best man available.

He was recommended a humble bachelor named Shun. Shun’s father was stupid; his stepmother deceitful; and his half-brother arrogant. Yet he lived in harmony with all of them.

On the strength of this recommendation, Yao gave Shun two of his daughters in marriage to observe his behaviour. Impressed by his virtue, Yao passed the throne to Shun and, before he died, told Shun “to impartially adhere to the middle way”

(允执厥中,

yun zhi jue zhong). During his reign, impressed by Yu’s qualities, including his success in taming the flood waters, Shun decided to pass the throne to Yu and, before his death, told Yu the yun zhi jue zhong.

What is "the middle way"?

"Middle" (中,

zhong) is to remain serene before the stirrings of joy, anger, sorrow or pleasure; "Harmony" (和,

he) is to express the emotions in proportion to the circumstance.

Thus, "Middle" is the great foundation for all under heaven; "Harmony" is the grand path for all under heaven. When "Middle" and "Harmony" are attained, Heaven and Earth will be at rest and all things will be nourished and will grow.

- Confucius, 500 BC

What is "all under heaven"?

"China is a continental country. To the ancient Chinese, their land was the world." And they have used expressions, such as "all under heaven" (i.e. "all beneath the sky") and "all within the four seas" to denote their world, i.e. their land.

"From the time of Confucius until the end of the 19th century, no Chinese thinkers had the experience of venturing out upon the high seas."

- Fung Yu-lan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 16.

The mother of all misunderstandings about China

China = "the Middle Kingdom" = "the Centre of the World" = the Ambition to "Rule the World"

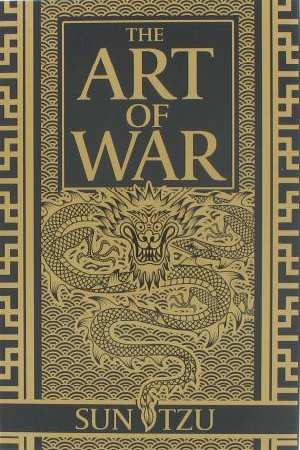

If the Chinese did not like war, why did they write The Art of War?

If you actually read The Art of War, you will find that the book is not about fighting and death. Instead, it stresses the evils of war and its great drain on the people so that the major aim in war is not the physical destruction of the enemy through massive bloodletting, but victory without engagement:

"Ultimate excellence lies not in winning every battle but in defeating the enemy without ever fighting. The highest form of warfare is to attack the enemy’s strategy; the next, to attack its alliances; the next, to attack its armies; the lowest form of war is to attack cities. Siege warfare is a last resort… The skilled strategist defeats the enemy without doing battle, captures the city without laying siege, and overthrows the enemy state without protracted war."

In essence, contrary to the Iliad, the Art of War

is about life.

“A ruler must never mobilise his men out of anger; a general must never engage in battle out of spite,”

says Sun Tzu because of the destruction war can bring about:

"Anger can turn to pleasure; spite can turn to joy. But a nation destroyed cannot be put back together again; a dead man cannot be brought back to life."

How different are the above words from the ancient Greek inspiration to stare death in the face every day!

Guided by Abstraction versus Living from Intuition

"For more than four thousand years the Chinese have lived in the same area," said John K. Fairbank

Both Alexander the Great and the First Emperor conquered a world, but why is Alexander the Great the most well-known hero in the West while the Chinese people have only regarded the First Emperor as a villain?

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great is the most well-known hero in the Western world. Even in North America, which Alexander did not conquer, there are nearly two dozen cities and towns named Alexander or Alexandria. By the time of his death in 323 BC, at the age of thirty-two, Alexander had travelled to the furthest reaches of the known world (across 22,000 miles or across America eight times from Alexandria, Virginia to Alexander Beach, Washington) and conquered an empire of more than two million square miles that stretched all the way from the River Danube in Europe to the Indus of what is now Pakistan. He had led his army across mountains, deserts, rivers and seas, and he had won victory after victory against impossible odds. And he did all this in little more than ten years!

It is therefore easy to see why he soon picked up the nickname by which he is still known today: “Mega-Alexandros”, which is Greek for “Alexander the Great”.

The First Emperor

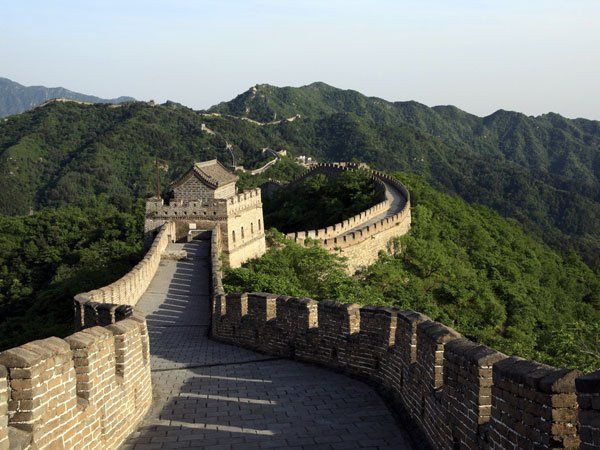

The “First Emperor” (Shi Huangdi) was the title chosen by the thirty-eight-year-old ruler of the Qin state after he, in a sudden hectic decade, led his state to annex one by one its six remaining rival states, ending the Warring States period and uniting China as one single country in 221 BC. With a population of twenty-one million, the empire of the First Emperor covered an area of one and a half million square miles, extending for a thousand miles westward of the pacific shore and from the deserts of the north to the lush lands south of the Yangtze River.

To defend against the invasion of nomads from the north, the First Emperor decided to incorporate a number of walls already existent along some of the former states’ northern frontiers in one continuous bulwark. Accomplished in little over ten years—just before he died in 210 BC, the end result was the Great Wall, a prodigious feast, over 2,500 miles long, across mountains and semi-desert.

Given the First Emperor’s parallel so far with Alexander the Great, you may be tempted to think that the people of China must have regarded him as a hero. But the exact opposite has been true: there has been a heroine, a steadfast young lady called Meng Jiangnu (孟姜女), associated with the Great Wall. The story goes:

"Soon after their marriage, Meng Jiangnu’s husband was confiscated to work on building the Great Wall, and the couple lost contact with each other for nearly a year. When winter came, she was worried that her husband might not be wearing enough clothing. So she made winter clothing and decided to take it to him. It was a very long journey, and she had to endure danger and countless hardships. But when she reached the Great Wall, she was told that her husband had already died of hunger and exhaustion and had been buried under the Great Wall. She cried and cried bitterly for days. And while she wept, sections of the Great Wall suddenly collapsed and her husband’s bones appeared amidst the rubble.

News of the collapse then reached the First Emperor who was on an inspection tour of the Great Wall. Attracted by the beauty of Meng Jiangnu, however, the Emperor asked her to become a concubine of his. She said that she would agree only if the Emperor held a proper funeral for her husband. At the end of the funeral, she told the Emperor: “You are a cruel tyrant to the people. Now that you have murdered my husband, how dare you ask me to become a concubine of yours?” She then held her husband’s bones in her arms and jumped into the sea."

Today, we find the Temple of Meng Jiangnu on a little mountain called Fenghuang Shan, four miles east of Shanhaiguan Pass at the very eastern end of the Great Wall. Inside the front hall, we find a coloured sculpture featuring Meng Jiangnu, with her expression revealing her grief and indignation and two maidens standing by her sides. On the two pillars by their sides, there is a couplet:

“How can the Qin First Emperor rest in peace while the construction of the Great Wall has produced such grievances? Meng Jiangnu is not dead because her loyalty bas been engraved on every stone through the ages.” Above her sculpture, there is a plaque, inscribed with four Chinese characters, wan gu liu fang, meaning

“an eternal good name”.

Although only a legend, people have admired Meng Jiangnu’s love for her husband and her rebellious spirit through the ages. The Temple of Meng Jiangnu at Shanhaiguan Pass had been built before the Song dynasty and repaired in the Ming dynasty. The walls inside the front hall are inscribed with poetry, letters, and calligraphy, including words of commemoration by Qing emperors Qianlong, Jiaqing and Daoguang. Many temples in the name of Meng Jiangnu also exist in other parts of the country, and she has been remembered in poetry, folk songs, and plays. Even the story itself has evolved; Wilt L. Idema’s timely book Meng Jiangnu Brings down the Great Wall

brings together ten versions of this most popular Chinese legend.

Why had the Qin ruler been able to unite China but unable to become a hero of the people?

This is most thoroughly explained in an essay entitled 过秦论 ("On the Failings of the Qin"). A classic to this present day, the essay was written by scholar-official Jia Yi in the early days of the Han dynasty (206 BC - AD 220), which succeeded the Qin dynasty established by the First Emperor.

By looking at the rise and fall of the Qin over a space of some one hundred years, Jia Yi identified

the perils of the ruler having blind faith in the use of force to achieve personal ambitions while ignoring the people’s wishes for peace and stability, with 仁义不施而攻守之势异也 (“the situation has changed from conquering to governing but benevolence and righteousness are not exercised”) becoming the most important motto for any ruler throughout the 2,500-year Chinese history.

The Han dynasty has often been compared to the Roman Empire, but the contrast between the two societies cannot be starker.

The Colosseum in Rome

The Zhaojun Tomb, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China

The Han dynasty was contemporaneous with the Roman Empire and has often been compared to it. For example, the

Cambridge Illustrated History of China says: "Han and Rome both had strong governments that expanded geographically, promoted assimilation, and brought centuries of stability to the central regions. Both managed to deal with enormous problems of scale, ruling roughly similar numbers of people over roughly similar expanses of land. Both developed bureaucratic institutions, staffing them with educated landowners. Both invested in the construction of roads, defensive walls, and waterworks. Both were threatened by barbarians at their frontiers and often used barbarian tribal units as military auxiliaries."

Yet,

“Roman society and culture were always militaristic,” says renowned historian J M Roberts, with

the omnipresence of the amphitheatre being “a standing reminder of the brutality and coarseness of which Roman society was capable.” From the time of Augustus, the army was a regular long-service force, where the ordinary legionary served for twenty years, four in reserve, and he more and more came from the provinces as time went by. ForRome became a self-perpetuating military machine: through treaties that gave a share of all war gains to her defeated or allied cities or communities, Rome had a huge supply of troops for its army.

More conquests gave more troops, which gave more ability to conquer, expanding Roman rule from a small city in central Italy to an empire extending from Armenia and Mesopotamia in the east to the Iberian Peninsula in the west, and from the Rhine, Danube, and British Isles in the north to Egypt and provinces on the Mediterranean coast of North Africa. Although trade and roads helped to draw most of Europe into a single empire, “it was in the camps of the legions that the heart of the empire lay,” with the expansion of Rome and her allies being likened to “a criminal gang: as long as the gang keeps stealing, everyone gets a share in the takings; but stop and the gang falls apart.”

The Han Dynasty

Despite the Great Wall, the Chinese were always under the aggressive attacks of the Xiongnu from the north, as vividly described by Sima Qian in the Shiji

(“Historical Records”), a work written about a hundred years after the construction of the Great Wall:

Everything about them seemed to be the opposite of the Chinese: they had no written language, family names, or respect for the elderly; they had no cities, permanent dwellings, or agriculture. Where the Xiongnu excelled was in warfare, for their men could all ride and shoot and would raid without hesitation: “When they see the enemy, eager for booty, they swoop down like a flock of birds.”

In the winter of 200 BC, the Han founding emperor Gaodi led an army to expel the Xiongnu but ended up being outnumbered and surrounded by the latter at Baideng, a place near today’s Datong, Shanxi province. The siege was only relieved seven days later after messengers were sent to bribe the wife of the Xiongnu leader Maodun Chanyu. Realising that the Han was not strong enough to confront the Xiongnu, Emperor Gaodi then embarked on a policy of “peace through marriage” (和亲, heqin), which involved sending a princess to marry the Xiongnu leader (sounds a mad idea after the Baideng escape) and giving him massive gifts of silk, grain, cash and other foodstuffs each year.

This conciliatory policy would stay in place for the next seventy years, but the peace secured was an uneasy one. Periodic humiliation of appeasement and gifting aside, the Han borders were still frequented by Xiongnu raids. In 166 BC during Emperor Wendi’s reign, 100,000 Xiongnu rough-riders reached a point less than one hundred miles from his capital, Changan. It was only after the accession of Emperor Wudi in 141 BC that other approaches were explored.

Above all, the plain failures of the conciliatory policy prompted Emperor Wudi to decide to take the offensive. Fortunately for him, the Han had by then had sufficient economic recovery. Not only was he able to appoint younger generals, such as Wei Qin and later Wei Qin’s nephew Huo Qubin, to recruit and train up soldiers, the Han also had an ample supply of warhorses for cavalry. In 127 BC, Wei Qin retook the fertile Hetao region (i.e. the Ordos Loop—the characteristic “n” shape that the Yellow River takes round the city of Ordos in Inner Mongolia, which forms parts of modern Shaanxi, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia) from the Xiongnu. Six years later, nineteen-year-old Huo Qubin expelled the Xiongnu from the Hexi Corridor, a long thin tongue of land above the Tibetan Plateau and below the Gobi Desert, with four commanderies established corresponding to modern Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan and Dunhuang of Gansu province.

During 115–60 BC, the Han and the Xiongnu competed for influence beyond Dunhuang, over the Tarim Basin oasis states (modern Xinjiang) as the Xiongnu had used them as a source of supplies since the Han-Xiongnu war began. In the end, the Han brought most of these small oasis states into tributary submission and established the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BC to deal with the region’s affairs. To flank the Xiongnu on their eastern border, Emperor Wudi also sent troops into northern Korea and established commanderies there. Meanwhile, in the south, Emperor Wudi reacted to border encroachments by sending out troops from 111 to 109 BC, and eventually turned the small kingdoms of Minyue (modern Fijian), Nanyue (modern Guangdong, Guangxi and North Vietnam) and Dian (modern Yunnan) into tributary states—thereby expanding the sphere of Chinese influence to the coastline for the first time.

Although the tribute system enabled the Han to secure peace with neighbouring states, Emperor Wudi’s large military campaigns had exhausted the national treasury and left his people poor—also reasons why he was “often accused of Legalist tendencies.” Poverty turned his people into bandits and thieves that ran rampant all over his empire. Late in his reign, Emperor Wudi began to regret the offensive approach he had taken towards border incursions. Perhaps most down-heartedly, despite earlier successes, Han campaign against the Xiongnu in Wuyuan (present Wuyuan County, Inner Mongolia) in 90 BC ended in disaster: not only was the Han army defeated, its commander Li Guangli even surrendered to the Xiongnu altogether.

Thus, when Sang Hongyang (the official in charge of finance) proposed in 89 BC that the Han should send soldiers to settle in Luntai of the Western Regions by engaging in both agriculture and defence, Emperor Wudi rejected it by issuing what is known to history as the "Repentance Edict of Luntai" (轮台罪已诏). “Only recently, somebody proposed that we raised an additional daily poll tax by 30 qian to be used for defending the frontiers. But this is to make the life of the old, the vulnerable, the lone and the orphan miserable,” the Edict states. “Now, it is proposed that we settle soldiers in Luntai, which is over a thousand li to the west of Cheshi. In our attack on Cheshi a while ago, although we won, thousands of our soldiers died as a result of the lack of food supply over the long distance.

I could not bear to think of somewhere even further west!” He went on to say in the Edict:

The most urgent thing for now is to forbid tax increases, return to the root occupation that is agriculture, and reward horse-raising only to compensate the losses in horses—enough to defend against raids by the Xiongnu. … Since accession to the throne, I have done much that is arrogant, causing misery and suffering to the country (天下, tianxia)—which I now profoundly regret. From now on, if anything causes suffering to the people or exhausts the resources of the country, we should not do it!

With Tian Qianqiu, who was in favour of resting the troops and the people and promoting agriculture, appointed as the new Chancellor-in-chief, and upon his recommendation, several agricultural experts made important members of the administration, this then was the turning point for the Han:

Emperor Wudi “committed the errors that had led to the fall of the Qin, but avoided the disastrous fall of the Qin.”

Emperor Wudi died two years later, but his successors maintained these policies. Inevitably, these policies (and the internal chaos caused by usurper Wang Mang) would encourage the Xiongnu to return so that by the second half of the first century, most states in the Tarim became allies of the Xiongnu again, and with their help, the Xiongnu began to raid the Hexi Corridor. It was in this context that there emerged Ban Chao (班超) from a historian’s family, who tired of literary pursuits and vowed to retake control of the Tarim. Chinese historical book records the following words of his: “A brave man has no other plan but to follow Fu Jiezi and Zhang Qian’s footsteps and do something and become somebody in a foreign land. How can I waste my life on writing?”

In 73, at the age of 41, he was dispatched with a small force. By playing on the internal dissensions among the states, he somehow succeeded, and soon turned them into tribute states again. In 91, he was made Protector General of the Western Regions, and did not return home until shortly before his death in 102. (It was also from the Tarim that in 97 he sent Gan Ying (甘英) as an emissary to Da Qin—presumably the Roman Empire. But after reaching the shores of the Persian Gulf and hearing scary tales about the sea, he abandoned his mission and returned to China, reporting that “the sea water is salty and cannot be consumed.”)

The story of Ban Chao would later only be remembered as “throw away your writing brush and join the military” while Fu Jiezi (who single-handedly killed the king of a small state in the Tarim in 77 BC to avenge his killing of a Chinese envoy under the influence of the Xiongnu) was to remain mostly obscure. They would, of course, have become celebrated heroes in the Western tradition, but just like the story of the legendary Meng Jiangnu, it was the story of another heroine that was to become part of the Chinese psyche: Wang Zhaojun (王昭君), one of the four China’s ancient beauties.

In 33 BC, when a Xiongnu Chanyu requested to become an imperial son-in-law to cement the relations of Han and his Xiongnu state, the emperor granted his request. However, unwilling to honour the Chanyu with his only daughter, the emperor asked for volunteers from his harem and promised to present her as his own daughter. Knowing that she would be wandering on the steppes, sharing a felt tent with her wild chieftain and drinking the hated fermented mare’s milk, Wang Zhaojun volunteered to go. During her life, she gave birth to a boy for the Xiongnu Chanyu and, following the local tradition, to two girls for his successor, and also taught the local people how to weave and farm. She became a very beloved in the Xiongnu and secured peace for the region for over sixty years.

After her death, she was buried by the Dahei River nine kilometres south of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, and today the Zhaojun Museum has been built around her tomb, which has been nicknamed “Green Mound”, referring to a phenomenon that in autumn, when grass and trees wither, those plants on the cemetery mound continue to prosper. On the top of the 33-metre mound, there is a small pavilion, within which we find a stele, with one side being inscribed with a portrait of hers and the other side with the words “Great Virtue” (大德, dade). In addition to the world’s only museum of Xiongnu culture, we also find, shortly after entering the Zhaojun Museum, a monument inscribed with a poem of the late deputy president of China Dong Biwu, written in 1963:

The name of Zhaojun has been known for a thousand years,

Peace-through-kinship between the Xiongnu and Han was high wisdom.

So many poets have expressed their own sentiments through Zhaojun,

But no amount of writings can express the true spirit of her story.

Indeed, beginning from poet Shi Chong in the third century, some 700 poems and 40 plays and folklores have been written by more than 500 famous writers to celebrate Wang Zhaojun. Some poems are written to describe her emotional struggling, while others focus on her physical beauty. But the poem by Tang poet Zhang Zhongsu in the late eighth century beautifully captures the peaceful scene in the border region rendered by her marriage:

The angel is married today;

The Xiongnu becomes peaceful.

Metal weapons are turned into ploughs;

The grassland is covered by countless cows and sheep.

In 1961, after visiting the tomb, the late modern historian Jian Bozan wrote a poem to celebrate the spirit of goodwill to bridge different cultures, even at the expense of one’s own interests, as embodied by Wang Zhaojun:

The achievement of Han Wudi had entered the history book,

But it owed to beacon fires along the ten-thousand-li Great Wall.

Thus, how could it compare to the music produced by the lute?

For no whistling arrows had since been heard of for fifty years!

What a contrast if we now look at the Western tradition: the Trojan War was fought because of the beauty of Helen!

Medieval Europe was the product of conquest, colonisation and Christianisation, while the Chinese, captive, took the victors captive.

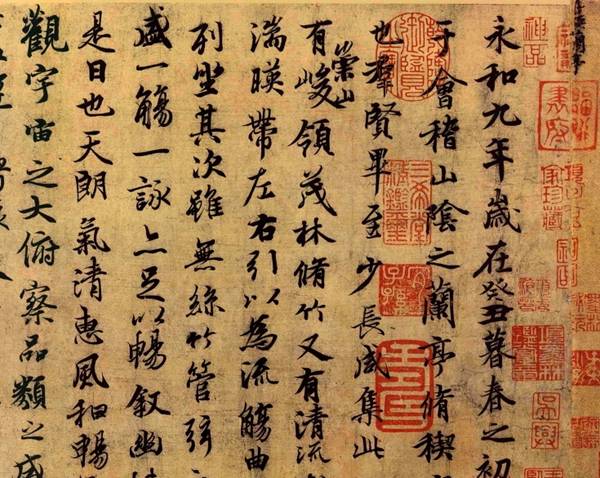

The most famous piece of calligraphy in Chinese history by far is the Record of Orchid Pavilion Gathering, written by Wang Xizhi in 353 (see right). He has been regarded as the "sage of Calligraphy".

Part of its fame is based on the story of how nearly three centuries later it got into the hands of the Tang emperor Taizong, one of the greatest rulers in China history.

Upon getting it, Taizong had many copies of Wang Xizhi's caligraphy made, but the original, we are told, he treasured so much that he had it interred with him in his grave.

The most famous piece of calligraphy in Chinese history by far is the Record of Orchid Pavilion Gathering, written by Wang Xizhi in 353 (see right). He has been regarded as the "sage of Calligraphy".

Part of its fame is based on the story of how nearly three centuries later it got into the hands of the Tang emperor Taizong, one of the greatest rulers in China history.

Upon getting it, Taizong had many copies of Wang Xizhi's caligraphy made, but the original, we are told, he treasured so much that he had it interred with him in his grave.

Europe: The Power of the Sword

Jesus (Matthew

10:34-39)

"Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to turn a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law—a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household.

Anyone who loves their father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; anyone who loves their son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. Whoever does not take up their cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Whoever finds their life will lose it, and whoever loses their life for my sake will find it."

The Process of Conquest, Colonisation and Christianisation

“Christianity is the only major religion to have as its central event the suffering and degradation of its god,” says Bamber Gascoigne on a 1977 Granada television series on the history of Christianity. It was after the Resurrection—and because of it— that the disciples of Jesus of Nazareth came to believe that he was the Son of God. “Whether they were right or wrong is a matter of opinion; something that you can no more prove than disprove.” All that matters, in terms of history, is that those first Christians believed that Jesus was God and that those who dedicate their lives to him could experience his supernatural power and eternal life.

Thousands of early Christians died for their new religious belief as they refused to attend the public ritual of making sacrifices to Roman gods (including the emperor)—the official religion for the sake of good luck. Yet, the public executions seemed to have reinforced the faith within the Christian community and stimulated curiosity and admiration among pagan onlookers. “If the Resurrection had been a fiction, the argument ran, the apostles would not have risked their lives for it,” said Henry Chadwick in his classic work The Early Church. As a result, Christianity had spread widely not only in towns but also in the countryside.

Still, it was due to the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine during his campaign against the invading barbarians, i.e. the Franks, near Autun in 311 that Christianity turned the crucial corner from heresy to orthodoxy. Before the battle, he allegedly saw a vision of a cross of light in the sky bearing the inscription, BY THIS SIGN THOU SHALT CONQUER, and immediately swore to worship the god of the Christians. Constantine duly won the battle on the occasion. Since 324, all Roman emperors, except Julian for three years, had been Christian.

Although women were among the first to be attracted to Christianity due to greater opportunities for community and welfare support, the means by which Christianity spread across Europe was generally “top-down”. When a non-Christian ruler was converted, he would be baptised along with his household and subjects. Clovis, king of the Franks, having married to a Christian Burgundian princess, on the eve of a battle promised that he would be converted if his wife’s God gave him victory. As a result, on Christmas Day, 496, he was baptised at Rheims, along with some 3,000 of his warriors. In much the same way, Christianity got established in England in 597.

By 1300, through conquest, marriage and colonisation, Frankish nobles had been established as the lords and power-brokers of practically every kingdom in Europe. The most enduring resistance was among the west Slav peoples of Poland and the eastern Baltic, but with the Lithuanian monarchy converting in 1386 in exchange for the Polish crown, the whole of Europe, with the exception of Granada in southern Spain, was finally brought into the Christian church.

But the spirit of the Latin-Frankish expansion is best expressed in the Crusades that began in 1095. The Crusader armies were a polyglot of nationalities and languages, but they were all led by families descended from Frankish nobility and thought of themselves as one people united in blood and religion. Like the Greeks and Romans, these Frankish leaders believed in the glory of war: “they did not stand on a hill and direct their men into battle; they strapped in their armour and led the charge.” Yet, Christianity also added a moral dimension to the idea of the glory of war.

“We shall slay for God’s love,” said one popular slogan of the crusaders.

Every death, on either side, would please God, as expressed by St Bernard of Clairvaux who stormed around preaching a crusade to the east, and became the most influential monk in the entire medieval period: “A Christian glories in the death of a Muslim because Christ is glorified. The liberality of God is revealed in the death of a Christian because he is led out to his reward.” In case any Christian wondered what the “reward” would be, Bernard spelt it out with the following powerful words in 1128:

"Rejoice, brave warrior, if you live and conquer in the Lord, but rejoice still more and give thanks if you die and go to join the Lord. This life can be fruitful and victory is glorious yet a holy death for righteousness is worth more. Certainly ‘blessed are they who die in the Lord’ but how much more so are those who die for Him."

In the Iberian peninsular, the clash of arms between Christians and Muslims that began in the early eighth century was transformed into a crusade as successive popes in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries accorded to Christian warriors willing to participate in the peninsular wars against Islam the same crusading benefits offered to those going to the Holy Land. But it was not until the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella that Christian Spain found a new unity, leading to the Christian conquest of Granada in 1492.

Almost instantly, the same process began to be extended to the rest of the world. Later in that year of 1492, Columbus set sail westward in the service of Ferdinan and Isabella, not only to find a shorter trade route to the far East or lands rich in gold, but to convert more infidels for Christ. “It would be a new crusade, along the same old lines—with that well-tried and powerful blend of courage, cruelty, idealism and greed,” said Gascoigne on his TV programme The Christians.

China: The Power of the Brush

Mencius

King Hui of Liang: 'How may the world be at peace?'

Mencius: 'When there is unity, there will be peace.'

King Hui of Liang: 'But who can unify the world?'

Mencius: 'He who does not delight in killing men can unify it.'

(Mencius, Ia, 6)

"Treat the aged in your family as they should be treated, and extend this treatment to the aged of other people's families. Treat the young in your family as they should be treated, and extend this treatment to the young of other people's families."

(Mencius, Ia, 7)

The Cycle of Unity-Disunity-Unity

It is amazing to think that Wang Xizhi's calligraphy not only represented the highest level in the art of writing with a brush but also is readily readable today to educated Chinese, while the modern form of English writing did not occur until a thousand years later. Even then, few English people today can read the writing of Geoffrey Chaucer, the "father of English literature".

The age Wang Xizhi lived in was already one of disunity, following the 400-year-unity achieved by the Han. According to Mencius, if a ruler lacks the ethical qualities that make a good leader, the people have the moral right of revolution. In practical terms, a new dynasty began with a clean slate. It had few commitments, and its prestige or strength was sufficient for it to gather more than adequate funds for its immediate needs. With the passage of time the imperial family grew larger and greedier, the official classes became used to luxury. Ever-increasing demands fell, ultimately, on the one group of people without influence, the peasants. When the system had deteriorated so far as to be intolerable, the peasants finally rose in rebellion.

Yet, given the perpetual threat from beyond China's northern frontier, peasant rebellions were almost always an invitation for invasions by the nomadic tribes. In 316, a great invasion of the nomadic peoples swept into China, causing the unstable Chinese court that emerged after the Han to flee south, so that from 316 to 589, while Chinese dynasties ruled at Nanjing over the south, the north was divided between the barbarian states - called the Sixteen Kingdoms - founded by the invading nomadic peoples.

Since these barbarian states were established on the principle of the tribal confederation, in which a supreme chief exerted authority through success in battle and the booty that he distributed to his followers, members of diverse tribes or lineages followed whoever was militarily successful so that any serious defeat or the death of the chief led to a rapid collapse. As such, none of them was capable of uniting the north, let alone conquer the south - despite the latter's lack of a strong army.

Although the period has been called the "Age of Confusion", there was one certainty: the art of Chinese writing and Chinese literature not only flourished but also acquired new forms. This was natural in the south, but in the north, the Chinese language did not die out, or become transformed, as happened to Latin, but continued very little affected by the languages of the invaders. This was undoubtedly because the north of China was the most populous area, had the oldest tradition of civilisation, and was the real stronghold of Chinese culture at that time.

The barbarians were unable to change this, unlike the western European barbarian invaders who changed the languages and character of the old western Roman provinces. On the contrary, the overwhelming Chinese majority absorbed the invaders and soon taught them Chinese ways and converted them into Chinese. As soon as this transformation had reached the point where there remained no obvious difference between a man of nomadic ancestry and one whose descent was from pure Chinese, the last reasons for separation disappeared. Thus, in 589, the new Sui dynasty reestablished the united empire.

Like the Qin, the Sui was short-lived because of the border wars launched by Wendi's second son, Yangdi. Replacing the Sui dynasty was the Tang dynasty, which was established by the Li family. Although Chinese on the father's side, the Li family had intermarried with the noble families of Tartar ancestry. As such, early Tang emperors, in particular, Taizong , succeeded in not only regaining the Tarim basin but also in pushing beyond Pamirs .

But for more than 600 years, the Tang and the succeeding dynasty Song would be renowned for fully developing the power of the brush. Famous for his enlightened government, Tang Taizong was also a great patron of literature, personally editing the histories of the previous age of division, establishing schools and the imperial academy. His calligraphy, an art much admired in China, is still reproduced as the model for school children.

The founder of the Song deliberately fostered the idea of a civil service based on talent alone so that in the early Song period all the best writers of either prose or poetry, with at the very most three exceptions, held senior posts in the administration. Su Dongpo, for example, can be taken as typical of the best elements of the Song dynasty. He was a fully rounded gentleman proficient in all the arts, When in office, he was fearless in speaking his opinion.

The concentration on the brush inevitably led to a situation, whereby the profession of solider had become despised and was to remain so for many centuries. Despite resisting the constant attacks from the Khitens and Jurchens from the north ever since its founding in 907, the Song was conquered by the Mongols in 1279.

Yet, the years of barbarian occupation had made little lasting difference to China. Confucianism had been made more rather than less attractive by those ninety years in the wilderness. The seizing the throne by a Chinese peasant in 1368 was in itself a pleasant echo of the founding of that most spectacular of the early dynasties, the Han.

Early Ming China's ships were by far the most advanced in the world, but why didn't the Chinese conquer Europe? Instead, Europeans conquered America.

Named after the “greatest explorer” of the Arab

world,

the

Ibn Battuta Mall in Dubai is dubbed “the world’s largest themed shopping mall”. The single level mall is divided into six zones, each reflecting the architecture of the regions that Ibn Battuta visited.

In the China Court, there

is a display, on the right, that suggests the relative sizes of Admiral Zheng He’s “treasure ships”

of the early 15th century and Columbus’ flagship, the Santa Maria—representative

of the ships used in Portuguese and Spanish maritime voyages later in the

century.

In the China Court, there

is a display, on the right, that suggests the relative sizes of Admiral Zheng He’s “treasure ships”

of the early 15th century and Columbus’ flagship, the Santa Maria—representative

of the ships used in Portuguese and Spanish maritime voyages later in the

century.

Inward-looking Ming China

Zheng He's Voyages

Of all the civilisations of premodern times, none appeared more advanced, none felt more superior, than that of China. Consider just two facts: Its considerable population, 100-130 million compared with Europe's 50-55 million in the fifteenth century; and its greatest seagoing fleet in the world

- in 1420, the Ming navy was recorded as possessing 1,350 combat vessels, including 400 large floating fortresses and 250 ships designed for long-range cruising. (The U.S. Navy today has only 430). Some of them were five times the size of the ships being built in Europe at the time.

To impress Ming power upon the world and show off China's resources and importance, the emperor Yongle sent the Treasure Fleet, under the command of the eunuch admiral Zheng He, on seven epic voyages through out the China seas and Indian Ocean, from Taiwan to the Persian Gulf and distant Africa.

The Treasure Fleet was vast - some vessels were up to 120 metres long. (Christopher Columbus's Santa Maria was only 19 metres.) A Chinese ship might have several decks inside it, up to nine masts, twelve sails, and contain luxurious staterooms and balconies, with a crew of up to 1,500, according to one description. On one journey, 317 of these ships set sail at once.

What then was Zheng He's goal? It was to disseminate the virtues of the Chinese emperor and forge friendships with neighbouring countries - and not to conquer, occupy and colonise them. The fleet carried Chinese silk, porcelain and lacquered goods abroad, and brought home, as tributes to the emperor, spices, herbs, rhinoceros horns, pearls, precious stones and rare woods. It was kind of trade but because the Chinese emperor wanted to show generosity and kindness above all, the expeditions cost the Ming dynasty much more than they brought in.

During the seven expeditions between 1405 and 1433, force was only used three times for three different reasons.

On the first expedition, Zheng He's forces managed to capture Chen Zuyi, a notorious Chinese pirate who had been terrorising the sea routes between the islands of what is now Indonesia. Five thousand pirates were killed in the battle, and Chen Zuyi was taken back to China and beheaded.

On the island of Java and in northern Sumatra, the Chinese accidentally got involved in a local civil war after landing on the shores of a rival tribe. Later, in Ceylon, after a local warrior refused the Zheng He's friendly gesture and sought to plunder his Treasure Fleet, Zheng He managed to seize him and took him back to China, where he was pardoned by the emperor and returned home.

The Aftermath

Three years after the final voyage in 1433, an imperial edict banned the construction of seagoing ships; later still, a specific order forbade the existence of ships with more than two masts. Zheng He's great warships were laid up and rotted away.

The reason for this decision was natural: the threat of the nomads from the north. Apart from the costs involved in maintaining a large navy, the Confucian code dictated that warfare itself was a deplorable activity

and that armed forces were made necessary only by the fear of barbarian attacks or internal revolts. In other words, defence on land was all that was required.

No wonder that by 1644, China was again conquered, this time, by the vigorous Manchus, a nomadic tribe based to the east of the Mongols.

The European Conquest of America

Christopher Columbus' Voyages

"Christopher means 'bearer of Christ', but for millions of American Indians he was the bearer of death,"

says David Reynolds in his bestseller America, Empire of Liberty. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore at the Bahama Islands, the Arawak Indians ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. But what Columbus wanted was one thing:

gold. He sailed to what is now Cuba, then to Hispaniola, where bits of visible gold in the rivers, and a gold mask presented to Columbus by a local Indian chief, led to wild visions of gold fields.

In his report to the Court in Madrid, he asked for a little help from their Majesties, and in return he would bring them from his next voyage "as much gold as they need... and as many slaves as they ask." He was full of religious talk: "Thus the eternal God, our Lord, gives victory to those who follow His way over apparent impossibilities."

As such, his second expedition was given 17 ships and more than 1,200 men, and the aim was clear: slaves and gold. In 1495, they went on a great slave raid, rounded up fifteen hundred Arawak men, women and children, put them in pens guarded by Spaniards and dogs, then picked the five hundred best specimens to load onto ships. Of those five hundred, two hundred dies on route. The rest arrived alive in Spain and were put up for sale by the archdeacon of the town. Columbus later wrote: "Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold."

In the province of Cicao on Haiti, where he and his men imagined huge gold fields to exist, they ordered all persons fourteen years or older to collect a certain quantity of gold every three months. When they brought it, they were given copper tokens to hang around their necks. Indians found without a copper token had their hands cut off and bled to death. As the only gold around was bits of dust garnered from the streams, they fled, were hunted down with dogs, and were killed.

Trying to put together an army of resistance, the Arawaks faced Spaniards who had armour, muskets, swords, horses. When the Spaniards took prisoners they hanged them or burned them to death. Among the Arawaks, mass suicides began, and infants were killed to save them from the Spaniards. In two years, through murder, mutilation, or suicide, half of the 250,000 Indians on Haiti were dead.

When it became clear that there was no gold left, the Indians were taken as slave labour on huge estates, known later as encomiendas. They were worked at a ferocious pace, and died by the thousands. By the year 1515, there were perhaps fifty thousand Indians left. By 1550, there were five hundred. A report of the year 1650 shows none of the original Arawaks or their descendants left on the island.

The Aftermath

What Columbus did to the Arawaks of the Bahamas, Cortes did to the Aztecs of Mexsco, Pizarro to the Incs of Peru, and the English settlers of Virginia and Massachusetts to the Powhatans and the Pequots.

Upon establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, governor John Winthrop created the excuse to take Indian land by declaring the area legally a "vacuum". And to justify their use of force to take the land, the Puritans appealed to the Bible, Romans 13:2: "Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God; and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation."

Thus began the history of the European invasion of the Indian settlements in the Americas. Two and a half centuries later, the U.S. was to dominate the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast.

Father Matthew Ricci's observation of Ming China

"Before closing this chapter on Chinese public administration, it would seem to be quite worth while recording a few more things in which this people differ from Europeans. To begin with, it seems to be quite remarkable when we stop to consider it, that in a kingdom of almost limitless expanse and innumerable population, and abounding in copious supplies of every description, though they have a well-equipped army and navy that could easily conquer the neighbouring nations, neither the King nor his people ever think of waging a war of aggression.

They are quite content with what they have and are not ambitious of conquest. In this respect they are much different from the people of Europe, who are frequently discontent with their own governments and covetous of what others enjoy. While the nations of the West seem to be entirely consumed with the idea of supreme domination, they cannot even preserve what their ancestors have bequeathed them, as the Chinese have done through a period of some thousands of years."

China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci: 1583 - 1610 (New York: Random House, 1942), pp. 54-55.

"Before closing this chapter on Chinese public administration, it would seem to be quite worth while recording a few more things in which this people differ from Europeans. To begin with, it seems to be quite remarkable when we stop to consider it, that in a kingdom of almost limitless expanse and innumerable population, and abounding in copious supplies of every description, though they have a well-equipped army and navy that could easily conquer the neighbouring nations, neither the King nor his people ever think of waging a war of aggression.

They are quite content with what they have and are not ambitious of conquest. In this respect they are much different from the people of Europe, who are frequently discontent with their own governments and covetous of what others enjoy. While the nations of the West seem to be entirely consumed with the idea of supreme domination, they cannot even preserve what their ancestors have bequeathed them, as the Chinese have done through a period of some thousands of years."

China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci: 1583 - 1610 (New York: Random House, 1942), pp. 54-55.

Newtonian astronomical instruments were "strange objects" in the eyes of Qing emperor Qianlong, China's wisest ruler.No wonder Qing China was conquered by nations of the West in 1900, including the USA.

The Rise and Fall of the Manchus:1640's - 1840's

The Manchus had owed their rise to a system of military organisation called the Eight Banners. Every man was enrolled in a Banner, had the duty ti serve in war and the right to rations from his Banner. This organisation was kept intact after the conquest, and the Bannermen (旗人 in Chinese) became the common name for Manchus. The Bannermen were settled around Beijing to protect the capital, and also in large garrisons, each with its own inner walled city, in principal provincial capitals. They were forbidden to engage in commerce or agriculture, serving purely as military and civil officials. This law was designed to keep them as a reserve military force ready to save the dynasty in case of rebellion.

The first Manchu emperors also undertook extensive wars along the norther frontier, and also to the north-west. Under Kangxi and his two successors, Yongzheng and Qianlong, all Mongolia was reduced to Manchu rule; the great region of Xingjiang, which China had not controlled since Tang times, was conquered and made into a Manchu province; Tibet was invaded and brought under Chinese suzerainty; Korea and Annam (norther Vietnam) were tributaries, as was Burma and even Siam (northern Thailand). Late in the eighteenth century, the armies of Qianlong invaded and conquered Nepal. The Chinese Empire had never been so extensive nor so populous.

Yet, these frontier wars should be seen as a continuation of the Manchus' nomadic martial spirit rather than as something inherent in Chinese cultural tradition. In fact, it was the latter that was to rapidly sinicise the Manchus. Although, to keep their own language alive, the Manchu Emperors wisely established the rule that all official documents had to be written in both languages, inscriptions were in two scripts, in practice, because of their education was centred on Chinese works of history and philosophy, Manchu would soon become virtually a dead language.

Kangxi conciliated the intelligentsia with his genuine love of Chinese literature and the commissioning of vast histories, including the History of the Ming, compilations and dictionaries. Everyday, he read extracts from the Chinese classics, and practised calligraphy and painting. His grandson, Qianlong, kept him as a model: he rose at 6 am, ate at 8 am and 2 pm, each meal only lasting 15 minutes. In the morning Qianlong dealt with official business, in the afternoon he read, painted or wrote verse. He was a good calligrapher and is credited with over 42,000 poems.

With peace established within the region of China itself, and the nomad enemies conquered and pacified, there remained no wars to wage. For nearly a hundred and fifty years, until the end of the eighteenth century, there was practically unbroken peace in the provinces of the Empire, a situation which had not been seen since Tang and Song times. So successful, so powerful at home, so rich and so self-satisfied were the Manchus that when, in 1793, Lord Macartney brought the best England could produce at the time, including Newtonian astronomical instruments and top-end English weapons, to Qianlong, the latter dismissed them by writing to King George III:

"There is nothing we lack... We have never set any value on strange or ingenious objects, nor do we need any more of your country's manufactures..."

However, the perceptive Lord Macartney could see that behind the facade of the magnificent court and the venerable Emperor Qianlong, then in his eighties, there was weakness and decay. Indeed, above all, the army began to decay; for the idle Bannermen, drawing rations, but doing no work, became slothful, useless parasites, who even lost their military skill as a long peace gave them no opportunity to use it. A land people, whose warrior Emperors had experience of war only in the vast inland regions of northern Asia, the Manchus also neglected the sea and its possible dangers.

The European nations seemed far away and in the eighteenth century were preoccupied with their own was and quarrels. Although the British were then conquering India, the Manchus seem to have ignored the implied threat to their own Empire. All these things were to come about within a generation of the death of Qianlong, and his successors were to pay dearly for this failure to move with the times.

Qing China Besieged by Western Nations:1840's - 1890's

"We have the power in our hands, moral, physical, and mechanical; the first, based on the Bible; the second, upon the wonderful adaptation of the Anglo-Saxon race to all climates, situations, and circumstances... the third, bequeathed to us by the immortal Watt. By his invention every river is laid open to us, time and distance are shortened."

Macgregor Laird wrote the above words in 1837, after he led an expedition into the interior of Africa, by the River Niger, in the steam-vessels that his family shipbuilding company Birkenhead had built. Two years later, the company built Nemesis, which was to determine the outcome of the Opium War between Britain and China during 1840-1842. The Nemesis left Portsmouth on 28 March, 1840, and was the first iron ship to round the Cape of Good hope. By the time she reached Macao on 25 November, 1840, the war had been going on, desultorily, for five months. If the tension between China and Britain was commercial in origin, its persistence was a consequence of the state of military technology.

At sea, Britain was invincible and could destroy any Chinese fleet or coastal fort. China, on the other hand, was a land empire with few interests beyond her shores and few cities along her coasts. As long as the Europeans were incapable of pushing their way inland, China was invulnerable. The steamer, with its ability to navigate upriver and attack inland towns, ended the long Anglo-Chinese stalemate. During the British attack on Canton (Guangzhou) in early February 1841, the Nemesis entered the inner passage, a labyrinth of narrow shallow channels that paralleled the main channel of the river, a place where no foreign warship had ever dared venture. While approaching Canton from the rear, she destroyed forts and junks at will and terrorised the inhabitants.

As the British victories in capturing Canton and, subsequently, Xiamen, Dinghai, Jinghai and Ningbo on the east coast in 1841 did not persuade the Chinese to sue peace, the British decided to strike at the Grand Canal - the jugular vein of China - the principal north-south route along which boatloads of rice from Sichuan province were sent to feed the population of Beijing, the capital. In June 1842, the Nemesis , towing the eighteen-gun Modeste, led the British fleet in the Yangtze, firing grape and canister at the Chinese crafts, which fled. The Nemesis and her sister Phlegethon

thereupon chased the fleeing boats, captured one junk and three paddle-wheelers, and set the rest on fire.

In July 1842, the British fleet reached Zhenjiang, at the intersection of the river and the Grand Canal. This time the court at Beijing realised its precarious situation and a few days later sent a mission to Nanjing to sign a peace treaty. Stem had carried British naval might into the very heart of China and led to her defeat.

China's signing of the Treaty of Nanjing with Great Britian in 1842 was, however, only the first of a series of crushing defeats she had suffered at the hands of Western powers:

1856-1860: The Arrow War (or the Second Opium War).

In the mid-1850s, while the Qing government was embroiled in trying to quell the Taiping Rebellion, the British, seeking to extend their trading rights in China, found an excuse (the Chinese boarding of the British-registered ship Arrow) to renew hostilities. The French decided to join the British military expedition, using as their excuse the murder of a French missionary in the interior of China in early 1856.

In October 1860, British and French forces captured Beijing, and plundered and then burned the emperor’s Summer Palace.In an outhouse on the palace grounds, the British found eighteenth-century manufactures in mint condition, including two English-made carriages, astronomical instruments, an English shotgun, and two howitzers engraved with "Woolwich 1782". They had all been gifts for the Qianlong Emperor from King George II, presented by Lord Macartney in 1793.

1884: The Sino-French War.

China was defeated at sea, and the great Fuzhou shipyard, which was built with French aid, was demolished.

1894-1895: The Sino-Japanese War.

China was defeated at sea and on land by Japan, which had newly embraced Western imperialism.

1900: The Boxer Catastrophe.

China was defeated by an Eight-Nation Alliance, including the USA.

The Encounter of Natives and Newcomers: 1640's - 1840's

The land John Winthrop declared as legally a "vacuum" was of course not a vacuum at all. In fact, the European colonisers confronted extensive, complex, and long-established native societies from the very start. The Indians, John Winthrop said, had not "subdued" the land, and therefore had only a "natural" right to it, but not a "civil right". A "natural right" did not have legal standing. The Puritans also appealed to the Bible, Psalms 2:8: "Ask of me, and I shall give thee, the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession."

The Puritans lived in uneasy truce with the Pequot Indians, who occupied what is now southern Connecticut and Rhode Island. But they wanted them out of the way; they wanted their land. And they seemed to want also to establish their rule firmly over Connecticut settlers in that area. The murder of a white trader, Indian-kidnapper, and troublemaker became an excuse to make war on the Pequots in 1636.

The English developed a tactic of warfare used earlier by Cortes even more systematically: deliberate attacks on noncombatants for the purpose of terrorising the enemy. Francis Jennings described Captain John Mason's attack on a Pequot village on the Mystic River:

"Mason proposed to avoid attacking Pequot warriors, which would have overtaxed his unseasoned, unreliable troops. Battle, as such, was not his purpose. Battle is only one of the ways to destroy an enemy's will to fight. Massacre can accomplish the same and with less risk, and Mason had determined that massacre would be his objective."

So the English set fire to the wigwams of the village. By their own account: The Captain also said, We must Burn Them; and immediately stepping into the Wigwam... brought out a Fire Brand, and putting it into the Matts with which they were covered, set the Wigwam on Fire." William Bradford, in his History of the Plymouth Plantation, describes John Mason's raid on the Pequot village:

"Those that scaped the fire were slain with the sword; some hewed to peeces, others rune throw with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatchte, and very few escaped. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fryer, and sente there of, but the vicotry seemed a sweete sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to inclose their enemise in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enimie."

As Dr Cotton Mather, Puritan theologian, put it: "It was supposed that no less than 600 Pequot souls were brought down to hell that day." The war continued. Indian tribes were used against one another, and never seemed able to join together in fighting the English. A ffotnote in Virgil Vogel's book The Land Was Ours

(1972) says: "The official figure on the number Pequots now in Connecticut is twenty-one persons."

Forty years after the Pequot War, Puritans and Indians fought again. This time it was the Wampanoags, occupying the south shore of Massachusetts Bay. Their chief, Massasoit, was dead. His son Wamsutta had been killed by Englishmen, and Wamsutta's brother Metacom became chief. The English found their excuse, a murder which they attributed to Metacom, and they began a war of conquest against the Wampanoags, a war to take their land. They were clearly the aggressors, but claimed they attacked for preventive purposes. When it was over, in 1676, the English had won, but they had lost six hundred men. Three thousand Indians were dead, When Metacom was captured, colonists displayed his severed head as a grim trophy of war.

The colonial period, in short, began a tragically persistent pattern of native peoples decimated by conflict, new diseases, and the relentless advance of white settlements. When the English first settled Martha's Vineyard in 1642, the Wampanoags there numbered perhaps three thousand. There were no wars on that island, but by 1764, only 313 Indians were left there. By 1800, the US Indian population stood at about 600,000, a pathetic remnant of the estimated 2.2 million on the eve of European colonisation.

"Manifest Destiny" and US Expansionism:1840's - 1890's

In 1845, as Mexico and the United States disputed their border, John L. O'Sullivan, A New York editor, proclaimed that it was

"America's "manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions".

"Manifest Destiny" was a slogan that captured the public imagination, signifying America's God-given right as the instrument of liberty and progress to occupy all the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific. As Mexico capitulated, the United States acquired some half-million square miles, including the present states of Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah. California, its population swollen by 1848 gold rush, entered the union in 1850. Within a single lieftime, a nation of thirteen states along the Atlantic coast had become a continent power, stretching from ocean to ocean.

With that, the "Manifest Destiny" crowd began to dream of an overseas empire. There was more than thinking: the American armed forces had made forays overseas. A State Department list, "Instance of the Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad 1798-1945" (presented by Secretary of State Dean Rusk to a Senate committee in 1962 to cite precedents for the use of armed force against Cuba), shows 103 interventions in the affairs of other countries between 1798 and 1895. A sampling from the list, with the exact description given by the State Department:

1852-53: Argentina.

Marines were landed and maintained in Buenos Aires to protect American interests during a revolution.

1853: Nicaragua.

To protect American lives and interests during political disturbances.

1853-54: Japan.

The "Opening of Japan" and the Perry Expedition. [The State Department does not give more details, but this involved the use of warships to force Japan to open its ports to the United States.]

1853-54: Ryukyu and Bonin Islands.

Commodore Perry on three visits before going to Japan and while waiting for a reply from Japan made a naval demonstration, landing marines twice, and secured a coaling concession from the ruler of Naha on Okinawa. He also demonstrated in the Bonin Islands. All to secure facilities for commerce.

1854: Nicaragua.

San Juan del Norte [Greytown was destroyed to avenge an insult to the American Minister to Nicaragua.]

1855: Uruguay.

U.S. and European naval forces landed to protect American interests during an attempted revolution in Montevideo.

1859: China.

For the protection of American interests in Shanghai.

1860: Angola,

Portuguese West Africa. To protect American lives and property at Kissembo when the natives became troublesome.

1893: Hawaii.

Ostensibly to protect American lives and property; actually to prompote a provisional government under Sanford B. Dole. This action was disavowed by the United States.

1894: Nicaragua.

To protect American interests at Bluefields following a revolution.

Thus, by the 1890's, there had been much experience in overseas probes and interventions. Calls for empire were echoing through the halls of Washington. "I firmly believe that when any territory outside the present territorial limits of the United States becomes necessary for our defence or essential for our commercial development, we ought to lose no time in acquiring it," said Senator Orville Platt of Connecticut in 1894.

To become a world power, the U.S. built a world-class navy. A gung-ho Theodore Roosevelt was put in charge of it, and he said in 1897 that "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one." The next year, taking a fancy to several Spanish colonies, including Cuba and the Philippines, the U.S. declared war on Spain. Rebel armies were already fighting for independence in both countries and Spain was on the verge of defeat. Washington declared that it was on the rebels' side and Spain quickly capitulated. But the U.S. soon made it clear that it had no intention of leaving, with Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana declared in 1900:

"The Philippines are ours forever... and just beyond the Philippines are China's illimitable markets... the Pacific is our ocean."

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the US sent 1,200 marines to China as part of the "China Relief Expedition" from eight Western nations, i.e. Britain (and British India), United States, Australian, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan.

Perhaps the most ironical way of demonstrating the Chinese's lack of martial spirit is the fact that many Beijing citizens volunteered to assist the forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance in the latter's taking of Beijing City on 14 August, 1900, as vividly shown in this background photo.

America's Addiction to War

Since its founding, the U.S. has been at war with some other country for all but 30 years.

The United States started out as 13 small and vulnerable colonies clinging to the east coast of North America. Over the next century, those original 13 states expanded all the way across the continent, subjugating or exterminating the native population and wresting Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California from Mexico. It fought a bitter civil war, and came late to both world wars. But since becoming a great power around 1900, it has fought nearly a dozen genuine wars and engaged in countless military interventions.

Today, the U.S. maintains the largest and most powerful military in history. U.S. warships dominate the oceans, its missiles and bombers can strike targets on every continent, and hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops are stationed overseas. Every few years the U.S. sends soldiers, warships and warplanes to fight in distant countries.

"Many countries go to war, but the U.S. is unique

in both the size and power

of its military and its propensity to use it."

Washington Rules: America's Path to Permanent War

by Andrew J. Bacevich

For the last half century, as presidents have come and gone, the basic edifice of U.S. national security policy has remained unchanged:

- A worldwide military presence;

- Armed forces configured not for defence but for global power projection; and